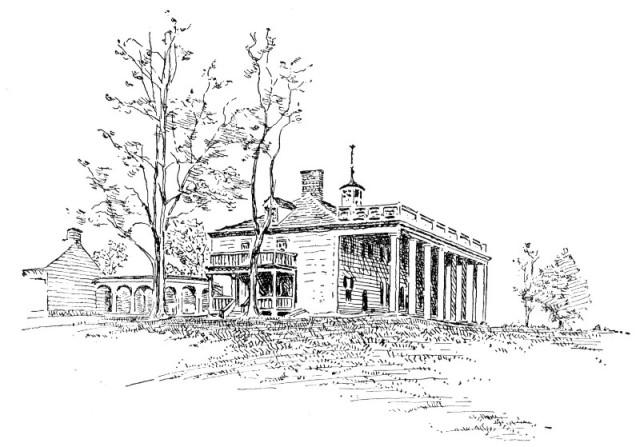

We left George Washington at Mount Vernon, his extensive plantation on the Virginia bank of the Potomac River. After his marriage with Mrs. Custis, who had large property of her own, Washington became a man of much wealth. He was at one time one of the largest landholders in America. As a manager of all this property, he had much to do. Let us delay our story a little to get a glimpse of the life led by him and other Virginia planters of his time.

The plantations were scattered along the rivers, sometimes many miles apart, with densely wooded stretches of land lying between. Each planter had his own wharf whence vessels, once a year, carried away his tobacco to England, and brought back in exchange whatever manufactured goods he required.

Nearly all his needs could be supplied at his wharf or on his plantation. His slaves included not only workers in large tobacco-fields, but such skilled workmen as millers, weavers, tailors, wheelwrights, coopers, shoemakers, and carpenters. Washington said to his overseers, "Buy nothing that you can make within yourselves." Indeed, each plantation was a little world in itself. Hence towns containing shops with goods and supplies of various kinds did not spring up much in Virginia.

The mansion of the planter, built of brick or wood and having at either end a huge chimney, was two stories high, with a large veranda outside and a wide hall-way inside. Near by were the storehouses, barns, workshops, and slave quarters. These last consisted of simple wooden cabins surrounded by gardens, where the negroes raised such things as vegetables and watermelons for their own use. In fact, the mansion and all the buildings clustered about it looked like a village. Here we could have seen, at all hours of the day, swarms of negro children playing happily together.

The planter spent most of his time in the open air, with his dogs and his horses. Washington gave to his horses rather fanciful names, such as Ajax, Blueskin, Valiant, and Magnolia, and to his dogs, Vulcan, Sweetlips, Ringwood, Forrester, and Rockwood. Outdoor recreations included fishing, shooting, and horse-racing.

Washington's Coach

Washington's Coach

Although life on the plantation was without luxury, there was everywhere a plain and homely abundance. Visitors were sure to meet a cordial welcome. It was no uncommon thing for a planter to entertain an entire family for weeks, and then to pay a similar visit in return with his own family. Social life absorbed much of Washington's time at Mount Vernon, where visitors were nearly always present. The planter, often living many miles away from any other human habitation, was only too glad to have a traveler spend the night with him and give news of the outside world. Such a visit was somewhat like the coming of the newspaper into our homes to-day.

A Stage Coach of the Eighteenth Century

A Stage Coach of the Eighteenth Century

We must remember that traveling was no such simple and easy matter then as it is now. As the planters in Virginia usually lived on the banks of one of the many rivers, the simplest method of travel was by boat, up or down stream. There were cross-country roads, but these at best were rough, and sometimes full of roots and stumps. Often they were nothing more than forest paths. In trying to follow such roads the traveler at times lost his way and occasionally had to spend a night in the woods. But with even such makeshifts for roads, the planter had his lumbering old coach to which, on state occasions, he harnessed six horses and drove in great style.

Washington was in full sympathy with this life, and threw himself heartily into the work of managing his immense property. He lived up to his favorite motto, "If you want a thing done, do it yourself." He kept his own books, and looked with exactness after the smallest details.

He was indeed one of the most methodical of men, and thus accomplished a marvelous amount of work. By habit an early riser, he was often up before daylight in winter. On such occasions he kindled his own fire and read or worked by the light of a candle. At seven in summer and at eight in winter he sat down to a simple breakfast, consisting of two cups of tea, and hoe-cakes made of Indian meal. After breakfast he rode on horseback over his plantation to look after his slaves, often spending much of the day in the saddle superintending the work. At two he ate dinner, early in the evening he took tea, and at nine o'clock went to bed.

As he did not spare himself, he expected faithful service from everyone. But to his many slaves he was a kind master, and he took good care of the sick or feeble. It may be a comfort to some of us to learn that Washington was fonder of active life than of reading books, for which he never seemed to get much time. But he was even less fond of public speaking. Like some other great men, he found it difficult to stand up before a body of people and make a speech. After his term of service in the French and Indian War he was elected to the House of Burgesses, where he received a vote of thanks for his brave military services. Rising to reply, Washington stood blushing and stammering, without being able to say a word. The Speaker, equal to the occasion, said with much grace, "Sit down, Mr. Washington, your modesty equals your valor, and that surpasses the power of any language to express."

While for many years after the close of the Last French War this modest, home-loving man was living the life of a high-bred Virginia gentleman, the exciting events which finally brought on the Revolution were stirring men's souls to heroic action. It was natural, in these trying days, that his countrymen should look for guidance and inspiration to George Washington, who had been so conspicuous a leader in the Last French War.

He represented Virginia at the first meeting of the Continental Congress in 1774, going to Philadelphia in company with Patrick Henry and others. He was also a delegate from his colony at the second meeting of the Continental Congress in May, 1775. On being elected by this body Commander-in-Chief of the American army, he at once thanked the members for the election, and added, "I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with." He also refused to receive any salary for his services, but said he would keep an account of the expenses he might incur, in order that these might be paid back to him.

On the 21st of June Washington set out on horseback from Philadelphia, in company with a small body of horsemen, to take command of the American army around Boston. Not long after starting they met a messenger bringing in haste the news of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Washington eagerly asked, "Did the Americans stand the fire of the regular troops?" "Yes," was the proud answer. "Then," cried Washington, gladly, "the liberties of the country are safe!"

Three days later, about four o'clock on Sunday afternoon, he reached New York, where he met with a royal welcome. Riding in an open carriage drawn by two white horses, he passed through the streets, escorted by nine companies of soldiers on foot. Along the route the people, old and young, received him with enthusiasm. At New Haven the Yale College students came out in a body, keeping step to the music of a band of which Noah Webster, the future lexicographer, then a freshman, was the leader. On July 2d, after arriving at the camp in Cambridge, Washington received an equally enthusiastic welcome from the soldiers.

Next day General Washington rode out on horseback and, under the famous elm still standing near Harvard University, drew his sword and took command of the American army. He was then forty-three years old, with a tall, manly form and a noble face. He was good to look at as he sat there, a perfect picture of manly strength and dignity, wearing an epaulet on each shoulder, a broad band of blue silk across his breast, and a three-cornered hat with the cockade of liberty in it.

Now came the labor of getting his troops into good condition for fighting battles, for his army was one only in name. These untrained men were brave and willing, but without muskets and without powder, they were in no condition for making war on a well-equipped enemy.

Moreover, the army had no cannon, without which it could not hope to succeed in an attack upon the British troops in Boston. By using severe measures, however, Washington soon brought about much better discipline. But with no powder and no cannon, he had to let the autumn and the winter slip by before making any effort to drive the British army out of Boston. When cannon and other supplies were at last brought down from Ticonderoga on sledges drawn by oxen, the alert American General fortified Dorchester Heights, which overlooked the city, and forced the English commander to sail away with all his army.

Washington believed that the next movement of the British would be to get control of the Hudson River and the Middle States. So he went promptly to New York in order to defend it against attack. But still his army was weak in numbers as well as in provisions, equipment, and training.

Washington had only about 18,000 men to meet General Howe, who soon arrived off Staten Island with a large fleet and 30,000 men. Not knowing where the British General would strike first, Washington had to be on his guard at many points. He had to prepare a defence of a line of twenty miles. He also built, on opposite sides of the Hudson River just above New York, Forts Lee and Washington.

When Brooklyn Heights, on Long Island, had been fortified, General Putnam went with half the army to occupy them. On August 27th General Howe, with something like 20,000 men, attacked a part of these forces and defeated them. If he had continued the battle by marching at once against the remainder, he might have captured all that part of Washington's army under Putnam's command. He might, also, have captured Washington himself, who, during the heat of the battle, had crossed over to Long Island.

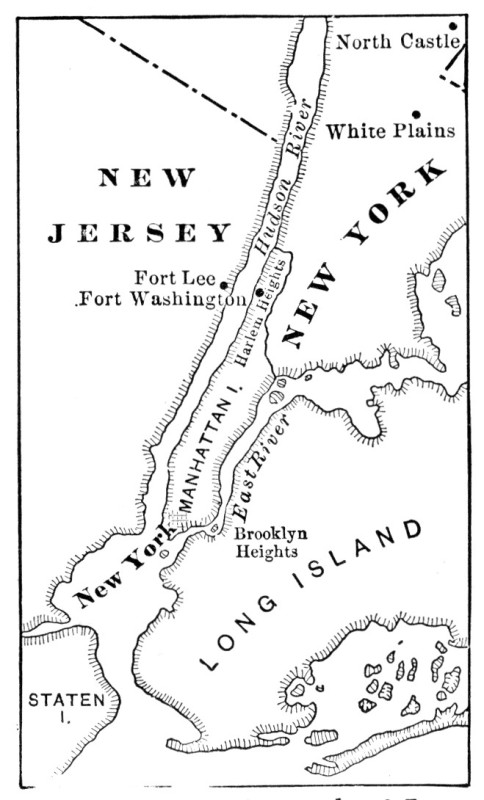

Map Illustrating the Battle of Long Island

Map Illustrating the Battle of Long Island

If Howe had done this, he might have ended the war at one stroke. But his men had fought hard at the end of a long night march and needed rest. Besides, he thought it would be easy enough to capture the Americans without undue haste. For how could they escape? Soon the British vessels would sail up and get between them and New York, when, of course, escape for Washington and his men would be impossible. This all seemed so clear to the easy-going General Howe that he gave his tired men a rest after the battle on the 27th. On the 28th a heavy rain fell, and on the 29th a dense fog covered the island.

But before midday of the 29th some American officers riding down toward the shore, noticed an unusual stir in the British fleet. Boats were going to and fro, as if carrying orders. "Very likely," said these officers to Washington, "the English vessels are to sail up between New York and Long Island, to cut off our retreat." As that was also Washington's opinion, he secured all the boats he could find for the purpose of trying to make an escape during the night.

It was a desperate undertaking. There were 10,000 men, and the width of the river at the point of crossing was nearly a mile. It would seem hardly possible that such a movement could, in a single night, be made without discovery by the British troops, who were lying in camp but a short distance away. The night must have been a long and anxious one for Washington, who stayed at his post of duty on the Long Island shore until the last boat of the retreating army had pushed off. The escape was a brilliant achievement and saved the American cause.

But this was only the beginning of Washington's troubles in this memorable year, 1776. As the British now occupied Brooklyn Heights, which overlooked New York, the Americans could not hold that place, and in a short time they had to withdraw, fighting stubbornly as they slowly retreated. Washington crossed over to the Jersey side of the Hudson, and left General Charles Lee with half the army at North Castle. The British captured Forts Lee and Washington, with 3,000 men, inflicting a severe loss upon the American cause. The outlook was gloomy, but more trying events were to follow.

In order to prevent the British from capturing Philadelphia, Washington put his army between them and that city. The British began to move upon him. Needing every soldier that he could get, he sent orders to General Lee to join him. Lee refused to move. Again and again Washington urged Lee to come to his aid. Each time Lee disobeyed. We now know that he was a traitor, secretly hoping that Washington might fail in order that he himself, who was second in command, might become Commander-in-Chief of the American army.

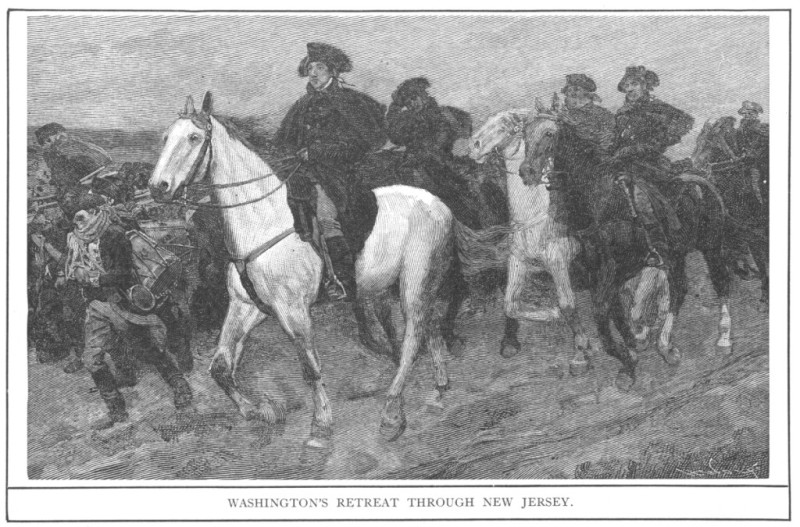

Lee's disobedience placed Washington in a critical position. In order to save his army from capture, Washington had to retreat once more, this time across New Jersey toward Philadelphia. As the British army, in every way superior to Washington's, was close upon the Americans, it was a race for life. Sometimes the rear-guard of the Americans was just leaving a burning bridge when the van of the British army could be seen approaching. But by burning bridges and destroying food supplies intended for the British, Washington so delayed them that they were nineteen days in marching about sixty miles.

Nevertheless the situation for the Americans was still desperate. To make matters worse, Washington saw his army gradually melting away by desertion. When he reached the Delaware River it numbered barely 3,000 men.

Washington's Retreat Through New Jersey.

Washington's Retreat Through New Jersey.

Having collected boats for seventy miles along the Delaware, Washington succeeded in safely crossing it a little above Trenton, on December 8th. As the British had no boats, they were obliged to wait until the river should freeze, when they intended to cross in triumph and make an easy capture of Philadelphia.

To most people, in England and in America alike, the early downfall of the American cause seemed certain. General Cornwallis--who in May of this year had joined the British army in America--was so sure that the war would soon come to an end, that he had already packed some of his luggage and sent it aboard ship, with the intention of returning to England at an early day.

But Washington had no thought of giving up the struggle. Far from being disheartened, he confronted the gloomy outlook with all his energy and courage. Fearless and full of faith in the patriot cause, he watched with vigilance for an opportunity to turn suddenly upon his over-confident enemy and strike a heavy blow.

Map Illustrating the Struggle for the Hudson River and the Middle States

Map Illustrating the Struggle for the Hudson River and the Middle States

Such an opportunity shortly came to him. The British General had carelessly separated his army into several divisions and scattered them at various points in New Jersey. One of these divisions, consisting of Hessians, was stationed at Trenton. Washington's quick eye noted this blunder of the British General, and he resolved to take advantage of it by attacking the Hessians at Trenton on Christmas night. Having been re-enforced, he now had an army of 6,000 and was therefore in a better condition to risk a battle. With 2,400 picked men he got ready to cross the Delaware River at a point nine miles above Trenton. There was snow on the ground, and the weather was bitterly cold. As the soldiers marched to the place of crossing, some of them with feet almost bare left bloody footprints along the route.

At sunset the troops began to cross. It was a terrible night for such an undertaking. Angry gusts of wind, and great blocks of ice swept along by the swift current, threatened every moment to dash in pieces the frail boats. From the Trenton side of the river, General Knox, who had been sent ahead by Washington, loudly shouted to let the struggling boatmen know where to land. Ten hours were consumed in the crossing. Much longer must the time have seemed to Washington, as he stood in the midst of the wild storm, his heart full of mingled anxiety and hope.

It was not until four o'clock in the morning that the troops were ready to march upon Trenton, nine miles away. As they advanced, a fearful storm of snow and sleet beat upon the already weary men. But they pushed forward, and surprised the Hessians at Trenton soon after sunrise, easily capturing them after a short struggle.

Washington had brought hope to every patriot heart. The British were amazed at the daring feat, and Cornwallis decided to make a longer stay in America. He soon advanced with a superior force against Washington, and at nightfall, January 2, 1777, took his stand on the farther side of a small creek. "At last," said Cornwallis, "we have run down the old fox, and we will bag him in the morning."

But Washington was too sly a fox for Cornwallis to bag. During the night he led his army around Cornwallis's camp, and pushing on to Princeton defeated the rear-guard, which had not yet joined the main body. He then retired in safety to his winter quarters among the hills about Morristown. During this fateful campaign Washington had handled his army in a masterly way. He had begun with defeat and had ended with victory.

In 1777 the British planned to get control of the Hudson River, and thus cut off New England from the other States. In this way they hoped so to weaken the Americans as to make their defeat easy. Burgoyne was to march from Canada, by way of Lake Champlain and Fort Edward, to Albany, where he was to meet not only a small force of British under St. Leger from the Mohawk Valley, but also the main army of 18,000 men, under General Howe, which was expected to sail up the Hudson from New York. The British believed that this plan would be easily carried out and would soon bring the war to a close.

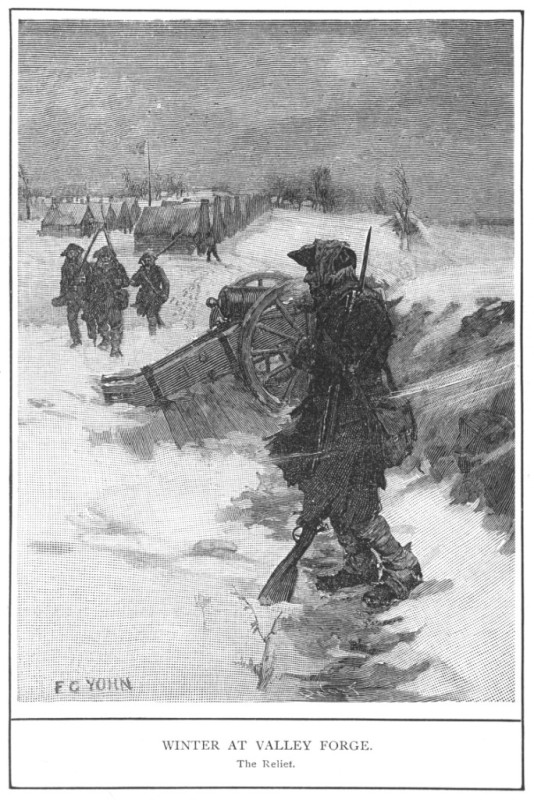

Winter At Valley Forge. The Relief.

Winter At Valley Forge. The Relief.

And this might have happened if General Howe had not failed to do his part. Instead of going up to meet and help Burgoyne, however, he tried first to march across New Jersey and capture Philadelphia. But when he reached Morristown, he found Washington in a stronghold where he dared not attack him. As Washington would not come out and risk an encounter in the open field, and as Howe was unwilling to continue his advance with the American army threatening his rear, he returned to New York. Still desirous of reaching Philadelphia, however, he sailed a little later, with his army, to Chesapeake Bay. The voyage took him two months.

When at length he advanced toward Philadelphia, he found Washington ready to dispute his progress at Brandywine Creek. There a battle was fought, resulting in the defeat of the Americans. But Washington handled his army with such skill that Howe spent two weeks in reaching Philadelphia, only twenty-six miles away.

When Howe arrived at the city he found out that it was too late to send aid to Burgoyne, who was now in desperate straits. Washington had spoiled the English plan, and Burgoyne, failing to get the much-needed help from Howe, had to surrender at Saratoga (October 17, 1777) his entire army of 6,000 regular troops. This was a great blow to England, and resulted in a treaty between France and America. After this treaty, France sent over both land and naval forces, which were of much service to the American cause.

At the close of 1777 Washington retired to a strong position among the hills at Valley Forge, on the Schuylkill River, about twenty miles northwest of Philadelphia. Here his army spent a winter of terrible suffering. Most of the soldiers were in rags, only a few had bed-clothing, and many had not even straw to lie upon at night. Nearly 3,000 were barefoot. More than this, they were often for days at a time without bread. It makes one heartsick to read about the sufferings of these patriotic men during this miserable winter. But despite all the bitter trials of these distressing times, Washington never lost faith in the final success of the American cause.

A beautiful story is told of this masterful man at Valley Forge. When "Friend Potts" was near the camp one day, he heard an earnest voice. On approaching he saw Washington on his knees, his cheeks wet with tears, praying to God for help and guidance. When the farmer returned to his home he said to his wife: "George Washington will succeed! George Washington will succeed! The Americans will secure their independence!" "What makes thee think so, Isaac?" inquired his wife. "I have heard him pray, Hannah, out in the woods to-day, and the Lord will surely hear his prayer. He will, Hannah; thee may rest assured He will."

We may pass over without comment here the events between the winter at Valley Forge and the Yorktown campaign, which resulted in the surrender of Cornwallis with all his army. Even when not engaged in fighting battles, Washington was the soul of the American cause, which could scarcely have succeeded without his inspiring leadership. But there is yet one more military event--the hemming in of Cornwallis at Yorktown,--for us to notice briefly before we take leave of Washington.

When at the close of his fighting with General Greene in the South, Cornwallis marched northward to Yorktown, Washington, with an army of French and American troops, was encamped on the Hudson River. He was waiting for the coming of a French fleet to New York. On its arrival he expected to attack the British army there by land, while the fleet attacked it by sea.

Upon hearing that the French fleet was on its way to the Chesapeake, Washington thought out a brilliant scheme. This was to march his army as quickly and as secretly as possible to Yorktown, a distance of 400 miles, there to join Lafayette and to co-operate with the French fleet in the capture of Cornwallis. The scheme succeeded so well that Cornwallis surrendered his entire army of 8,000 men on October 19, 1781.

This was the last battle of the war, although the treaty of peace was not signed until 1783. By that treaty the Americans won their independence from England. The country which they could now call their own extended from Canada to Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River.

Washington, tired of war, was glad to become a Virginia planter once more. But he was not permitted to live in quiet. After his retirement from the army his home became, as he himself said, a well-resorted tavern. Two years after the close of the Revolution he wrote in his diary: "Dined with only Mrs. Washington, which I believe is the first instance of it since my retirement from public life."

When, on the formation of the Constitution of the United States, the American people looked about for a President, all eyes naturally turned to George Washington. He was elected without opposition and was inaugurated at New York, then the capital of the United States, on April 30, 1789.

Washington's Home--Mount Vernon.

Washington's Home--Mount Vernon.

His life as President was one of dignity and elegance. It was his custom to pay no calls and accept no invitations, but between three and four o'clock on every Tuesday afternoon he held a public reception. On such occasions he appeared in court-dress, with powdered hair, yellow gloves in his hand, a long sword in a scabbard of white polished leather at his side, and a cocked hat under his arm. Standing with his right hand behind him, he bowed formally as each guest was presented to him.

After serving two terms as President with great success he again retired in 1797 to private life at Mount Vernon. Here he died on December 14, 1799, at the age of sixty-seven, loved and honored by the American people.

Review Outline

Washington At Mount Vernon, The Plantation In Virginia, The Planter's Mansion And Its Surroundings, Virginia Hospitality, Modes Of Travel, Washington's Working Habits, Appointed Commander-In-Chief Of The American Troops, General Washington And His Army, The British Driven From Boston, Washington Goes To New York, Battle Of Long Island, Washington's Escape From Long Island, The Traitor Lee Disobeys Washington, Washington Retreats Across New Jersey, A Gloomy Outlook, A Terrible Night Followed By A Glorious Victory, The British Plans In 1777, General Howe Fails To Do His Part, Burgoyne's Surrender; Aid From France, Washington At Valley Forge, The Surrender Of Cornwallis; Treaty Of Peace, Washington As President.

To The Pupil

1. By all means make constant use of your map.

2. Write on the following topics: the plantation, the planter's mansion, Virginia hospitality, modes of travel.

3. What was Washington's favorite motto? What were his working habits?

4. Describe Washington at the time when he took command of the army. What was the condition of this army?

5. Tell about Washington's troubles and his retreat across New Jersey?

6. Imagine yourself one of Washington's soldiers on the night of the march against the Hessians at Trenton, and relate your experiences. Try to form vivid pictures before you tell the story.

7. What were the British plans for 1777, and in what way did General Howe blunder in carrying out his part?

8. Describe the sufferings of the soldiers at Valley Forge.

9. Give a short account of Washington.

10. What were the leading causes of the Revolution? Its most striking result?